How my low GM prep has helped with emergent gameplay

I love GMing games. It’s so much fun to play the world. Creating NPCs makes me part of the shared story. Thinking up obstacles fleshes out the world my head’s imagining. And following the butterfly effect as the party crashes through the world, heedless of consequences, is an absolute blast. GMing may be one of the most fun things I’ve ever done, and I recommend all folks in the hobby to try taking a turn “behind the screen.”

On the other hand, GMing can be a lot of work. Maps have to be created, encounters populated, and environments described. GMs who use terrain may have to pull down assets off the shelf, or create new ones, and make sure the needed minis are available. In a world of VTTs maps don’t just need to exist, people expect them to be dressed so the immersion is a visual spectacle. And even if I’m committed to running theatre of the mind, or am planning to run a pre-written adventure, there’s still a good deal of prep to do. I need to populate a crawl, gather stat blocks, and make sure I’m familiar with the adventure so I’ll be free to let it breathe during the session.

I enjoy this process, but it takes time—and time is a resource I often lack. And this is this is why I’ve been experimenting with a concept of prep I’m calling “chaos sessions.”

In a chaos session I come to the table with no plan. I don’t know where the session will begin, what the problem is that will trigger an adventure, how that problem will be introduced, where the problem is located, how long it will take the reach the location, or what environments or obstacles the party will face along the way.

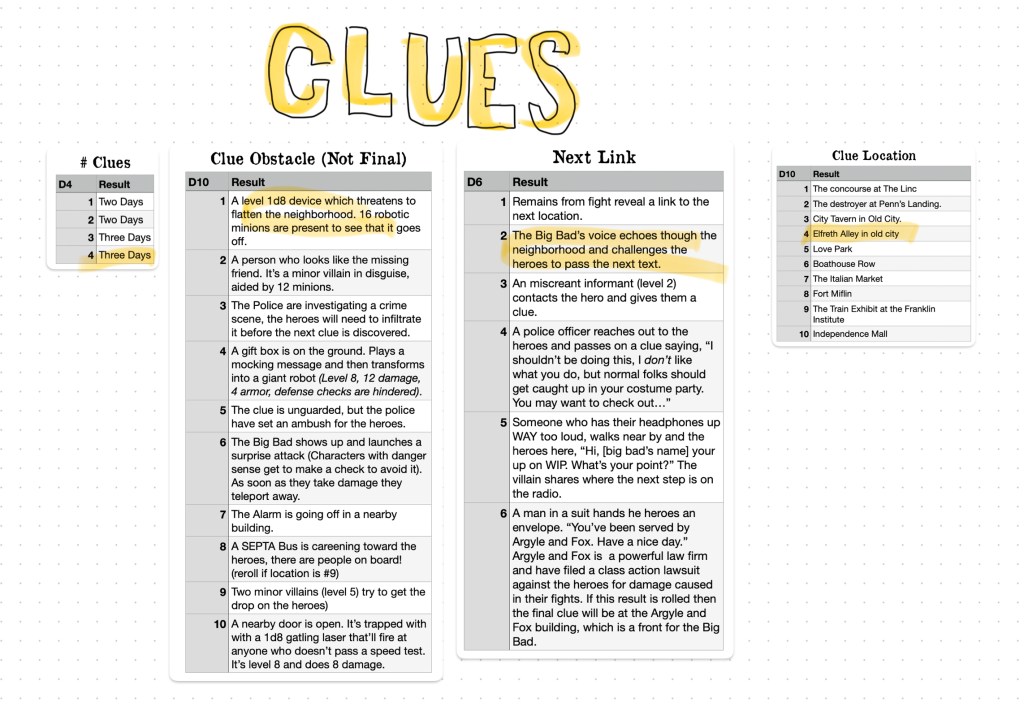

Instead, I create tables which will answer all those questions at the table. I’m still working on the process, but here’s how I’ve made it work so far. It’s not no prep, but it’s a fun way for me to do minimal prep. It’s also not a new concept, games have been doing this for years, but it’s one with which I’m having a lot of fun.

Step One: The Opening

The first table I create is the adventure’s starting point. I add as many as I can, with varying options to give the players different opportunities for interaction. I’ve included “typical” starting points like putting the party at the local tavern or in a family home, and I’ve included options like a local coffee shop’s poetry night.

The next table defines the adventure’s problem. This is whatever the “big bad” is trying to accomplish and doesn’t have to be a huge, earth shattering, event. Local problems can serve a great fodder for adventures. The “problem” can be as simple a fetch quest which the big bad attempts to thwart, or be a mysterious delivery mission that leaves the party pondering the best way forward. But if you want to go big, you can include options like an impending disaster or an invasion. Anything that creates drama which needs to be resolved can be added to the table.

My opening scene tables are then rounded out with a third table populated with various ways the problem is introduced to the party—events such as angelic visits, scientists bearing dire warnings, or desperate family members can show up to hook the players in. I’ll roll on this table after the party has had a chance to role play in the adventure’s starting point.

Step Two: The Journey

The journey begins by determining how many segments will the party will need to traverse to arrive where the problem can be resolved. This table is weighted to make the number of steps work within the framework of the group. For a regular at home, multi hour, session I could set things up to take anywhere from a couple of days to over a week. But for online play, one shots, or shorter sessions I’ve tended to cap this number out at three.

Then come the biome options, as well as a means of travel when it’s appropriate. Boat trips down river, a road through a forest, and traversing through a desert are all options I’ve used. I have a lot of fun making these up, though I’ve yet to roll on the option I believe would be the most fun—the back of a dragon who resents being used as a transportation service. This table doesn’t need to be rolled each day. If I want the party moving through a desert for a whole week, I can just leave them there. If things drag on I can always change the narrative for the next segment by making a new roll.

For each segment of the journey will encounter something along the way, which means I need another table!

This is the table a lot of TTRPG folks are used to, the “random encounter.” Entries on this channel can be something as dangerous as a large monster, as unnerving as a sudden weather change, or something lite-hearted like a man running a card game scam near where the party is traveling. Obstacles don’t have to lead to fights, nor must they require a great deal of effort to overcome. They just need to be something with which the players will need to interact.

I also create a table with different weather patterns, and effects, that the party will encounter each day—though I can ignore weather that doesn’t make sense in a particular biome. Three days of rain in a desert, for example, doesn’t really fit. It helps add a bit of color and can make things easier, or harder, depending on the weather. Kind of like real life.

This kind of travel has been a lot of fun for me to run. It creates a whole lot of oddball settings and encounters which are a blast to weave together into a narrative with the players.

Even better, whenever the day’s obstacle is overcome I open up the floor for the players to tell me what they’re doing before the next journey segment begins. This often leads to a whole other level of hijinks the players get to create on their own. The first time I ran this style of game, over on Dave Ward’s Grimwood Games channel, we ended up with two players joining an underground fight club, another sold a snake-oil solution to that fight club, and the remaining player wound up at a tea party with a bunch of little girls. We still don’t know how the last one happened, he was just there on a street corner trying to not smash the cup.

Step Three: The Destination

What happens when the party arrives at its destination? To figure it out, I need some more tables!

First, I roll to see how many rooms the destination will have. I can set this to anything I want, though the die type and results will reflect how big the place is likely to be. If I want to create a large crawl I can roll d100 and weight it so that the place may have 20-40 areas to explore. If I’m running a one shot and want things to get over quick, I can roll a d6 and weight the results to have no more than 4 areas. These can be rooms, levels, forest clearings, whatever fits the story up to that point.

Exploration isn’t fun if every area looks the same, so I also create a table with a number of different descriptions. I’ll populate this with locations like shrines, pillared halls, old barracks, crypts, natural caves, old kitchens, natural watering holes, and hidden dells. If adjoining locations don’t make sense I can either just ignore a result and re-roll or work them into the fiction somehow. A natural cave off a barracks that’s in an old mansion, for example, may just be an old root cellar.

Each area in the final exploration needs to include something with which the party must interact. So I create a table populated with obstacles the party will have to overcome. These are fun to think up. A room could be bisected by a bottomless pit, an ancient trap of varying lethality could be waiting to be triggered, the big bad’s minions could have an ambush set up, or the perhaps the Big Bad shows up for a hit and run attack just to keep the party off balance.

Step Four: The End

The “Big Bad Evil Guy” is a common TRPG trope. While this chaos method lends itself well including some big bad at the end of the adventure, it doesn’t necessarily have to be an “evil guy.” It could be the disaster which needs to be halted, for example.

In the “Big Bad” table, which I can roll whenever the narrative requires it, I’ll include common tropes like “the evil wizard,” some things are expected. But I will also add rows which include oblivious folks who have no idea they triggered a disaster by poking around, or a jaded civil servant who’s trying to get what they think they’re owed. It’s up to the dice to find out who, or what, is at the end of the journey.

Conclusion

I’ve had a lot of fun running this style of game, and have used this method for four sessions. Two were actual play live streams and the other two were for a lunchtime session I run for some pastors. Thus far I’ve used it only with Cypher System, since the Cypher’s “everything is a level” makes it easy to improvise everything on the fly, but I’d love to try it for Sentinel Comics RPG or Dragonbane as some point because I think it would work rather well.

I’ve also found that this method is very helpful for world building.

During my two actual plays we fleshed out the starting town’s geography. A river runs through it, flowing South to North. To the North is a forest, which takes two days travel to pass through by boat, and beyond the forest are hilly grasslands. To the South of the town is a desert, leading to mountains. Session one’s hijinks added a host of NPCs who were impacted by the characters, which were added into the obstacle tables in the second session. The rolls were favorable and some of those NPCs came calling in our second session, but if they hadn’t I’d have just left them in until they eventually popped up.

My lunchtime superhero sessions have allowed the players to create a fictional super power response organization (CHAT: Creative Hero Attack Team), an NPC bar owner named Phil (who is a lonely hero’s confident), and Phil’s seedy bar, in Philly, where the heroes can now hang out (and it might become a weighted starting point as their story continues).

As you can see, as we’ve played, the world has emerged. And all I did is set up some tables to let chaos do its thing. What a blast.